Third Trimester Bleeding (Antepartum Haemorrhage)

1:49:00 AM

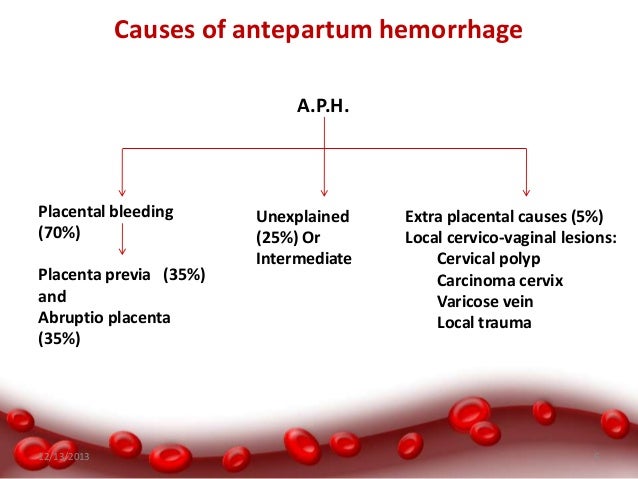

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) is defined as bleeding from or in to the genital tract, occurring from 24+0

weeks of pregnancy and prior to the birth of the baby. The most important causes of APH are placenta praevia

and placental abruption, although these are not the most common. APH complicates 3–5% of pregnancies and

is a leading cause of perinatal and maternal mortality worldwide. Up to one-fifth of very preterm babies are

born in association with APH, and the known association of APH with cerebral palsy can be explained by

preterm delivery.

Obstetric haemorrhage remains one of the major causes of maternal death in developing countries and is the cause of up to 50% of the estimated 500 000 maternal deaths that occur globally each year. Obstetric haemorrhage encompasses both antepartum and postpartum bleeding.

There are no consistent definitions of the severity of APH. It is recognised that the amount of blood lost is often underestimated and that the amount of blood coming from the introitus may not represent the total blood lost (for example in a concealed placental abruption). It is important therefore, when estimating the blood loss, to assess for signs of clinical shock. The presence of fetal compromise or fetal demise is an important indicator of volume depletion.

For the purposes of this guideline, the following definitions have been used:

Recurrent APH is the term used when there are episodes of APH on more than one occasion

Obstetric haemorrhage remains one of the major causes of maternal death in developing countries and is the cause of up to 50% of the estimated 500 000 maternal deaths that occur globally each year. Obstetric haemorrhage encompasses both antepartum and postpartum bleeding.

There are no consistent definitions of the severity of APH. It is recognised that the amount of blood lost is often underestimated and that the amount of blood coming from the introitus may not represent the total blood lost (for example in a concealed placental abruption). It is important therefore, when estimating the blood loss, to assess for signs of clinical shock. The presence of fetal compromise or fetal demise is an important indicator of volume depletion.

For the purposes of this guideline, the following definitions have been used:

- Spotting – staining, streaking or blood spotting noted on underwear or sanitary protection Minor haemorrhage – blood loss less than 50 ml that has settled

- Major haemorrhage – blood loss of 50–1000 ml, with no signs of clinical shock

- Massive haemorrhage – blood loss greater than 1000 ml and/or signs of clinical shock

Recurrent APH is the term used when there are episodes of APH on more than one occasion

What is the role of clinical assessment in women presenting with APH?

The role of clinical assessment in women presenting with APH is first to establish whether urgent

intervention is required to manage maternal or fetal compromise. The process of triage includes history

taking to assess coexisting symptoms such as pain, an assessment of the extent of vaginal bleeding,

the cardiovascular condition of the mother, and an assessment of fetal well being.

Women presenting with a major or massive haemorrhage that is persisting or if the woman is unable to

provide a history due to a compromised clinical state, an acute appraisal of maternal well being should be

performed and resuscitation started immediately. The mother is the priority in these situations and should be

stabilised prior to establishing the fetal condition.

If there is no maternal compromise a full history should be taken.

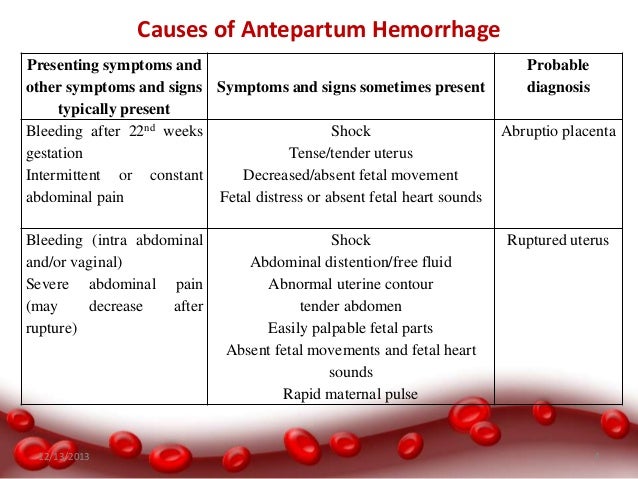

● The clinical history should determine whether there is pain associated with the haemorrhage. Placental abruption should be considered when the pain is continuous. Labour should be considered if the

pain is intermittent.

● Risk factors for abruption and placenta praevia should be identified.

● The woman should be asked about her awareness of fetal movements and attempts should be made to

auscultate the fetal heart.

● If the APH is associated with spontaneous or iatrogenic rupture of the fetal membranes, bleeding from a

ruptured vasa praevia should be considered.

● Previous cervical smear history may be useful in order to assess the possibility of a neoplastic lesion of the

cervix as the cause of bleeding.

The presentation of cervical cancer in pregnancy depends on the stage at

diagnosis and lesion size; most women with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

stage I cancer are asymptomatic; symptomatic pregnant women usually present with APH (mostly postcoital)

or vaginal discharge.

In a Swedish population study, the incidence of cervical cancer was 7.5 cases per

100 000 deliveries; in over half of these cases, the women had an abnormal cervical smear history.

Examination of the woman should be performed to assess the amount and cause of APH.

The basic principles of resuscitation should be adhered to in all women presenting with collapse or major

haemorrhage.

The primary survey should follow the structured approach of airway (A),

breathing (B) and circulation (C). Following initial assessment and commencement of resuscitation, causes for

haemorrhage or collapse should be sought.

All women presenting with APH should have their pulse and blood pressure recorded.

Abdominal palpation

The woman should be assessed for tenderness or signs of an acute abdomen. The tense or ‘woody’ feel to the

uterus on abdominal palpation indicates a significant abruption. Abdominal palpation may also reveal uterine

contractions. A soft, non-tender uterus may suggest a lower genital tract cause or bleeding from placenta or

vasa praevia.

A speculum examination can be useful to identify cervical dilatation or visualise a lower genital

tract cause for the APH. In a prospective observational study of 564 women presenting with APH,

521 (92.4%) underwent an admission speculum examination; 389 women (69%) had a normal

cervix, 120 (21%) had cervical ectropion and 12 (2%) had a dilated cervix. If the woman presents with a clinically suspicious cervix she should be referred for colposcopic

evaluation

Digital vaginal examination

If placenta praevia is a possible diagnosis (for example, a previous scan shows a low placenta, there is a high

presenting part on abdominal examination or the bleed has been painless), digital vaginal examination should

not be performed until an ultrasound has excluded placenta praevia. Digital vaginal examination can provide

information on cervical dilatation if APH is associated with pain or uterine activity.

What investigations should be performed in women presenting with APH?

Maternal investigations

Investigations should be performed to assess the extent and physiological consequences of the APH.

The maternal investigations performed will depend on the amount of bleeding.

The Kleihauer test should be performed in rhesus D (RhD)-negative women to quantify fetomaternal

haemorrhage (FMH) in order to gauge the dose of anti-D immunoglobulin (anti-D Ig) required.

The Kleihauer test is not a sensitive test for diagnosing abruption.

Ultrasound can be used to diagnose placenta praevia but does not exclude abruption. Placental abruption is a clinical diagnosis and there are no sensitive or reliable diagnostic tests

available. Ultrasound has limited sensitivity in the identification of retroplacental haemorrhage.

Blood tests

In cases of major or massive haemorrhage, blood should be analysed for full blood count and coagulation

screen and 4 units of blood cross-matched. Urea, electrolytes and liver function tests should be assayed. The

initial haemoglobin may not reflect the amount of blood lost and therefore clinical judgement should be used

when initiating and calculating the blood transfusion required. In such circumstances a point of care test

(‘bedside test’) to assess haemoglobin may be useful.

The platelet count, if low, may indicate a consumptive

process seen in relation to significant abruption; this may be associated with a coagulopathy.

In minor haemorrhage, a full blood count and group and save should be performed.

A coagulation screen is

not indicated unless the platelet count is abnormal.

In all women who are RhD-negative, a Kleihauer test should be performed to quantify FMH to

gauge the dose of anti-D Ig required.

The Kleihauer test is not a sensitive test for diagnosing placental abruption.

Ultrasound scan

Women presenting with APH should have an ultrasound scan performed to confirm or exclude placenta

praevia if the placental site is not already known. Ultrasound scanning is well established in determining

placental location and in the diagnosis of placenta praevia.

The sensitivity of ultrasound for the detection of retroplacental clot (abruption) is poor. Glantz and

colleagues reported the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of

ultrasonography for placental abruption to be 24%, 96%, 88% and 53% respectively. Thus,

ultrasonography will fail to detect three-quarters of cases of abruption. However, when the

ultrasound suggests an abruption, the likelihood that there is an abruption is high.

Fetal investigation

An assessment of the fetal heart rate should be performed, usually with a cardiotocograph (CTG) in

women presenting with APH once the mother is stable or resuscitation has commenced, to aid decision

making on the mode of delivery.

Whenever possible, CTG monitoring should be performed where knowledge of fetal condition will

influence the timing and mode of delivery.

Ultrasound should be carried out to establish fetal heart pulsation if fetal viability cannot be detected

using external auscultation.

APH, particularly major haemorrhage and that associated with placental abruption, can result in fetal

hypoxia and abnormalities of the fetal heart rate pattern. If the fetal heart rate cannot be heard on

auscultation, then an ultrasound scan should be performed to exclude an intrauterine fetal death.

Ultrasound imaging can be technically difficult, particularly in the presence of maternal obesity,

abdominal scars and oligohydramnios, but views can often be augmented with colour Doppler.

Guidance directly relevant to monitoring the fetal heart rate at the extreme of viability can be

reasonably extrapolated from advice on the management of women in extremely preterm labour

(less than 26+0 weeks) from the British Association of Perinatal Medicine.

The results of this working

group suggest ‘If active obstetric intervention in the interests of the fetus is not planned, for example

at gestations less than 26+0 weeks, continuous monitoring of the fetal heart rate is not advised. There is a lack of published evidence regarding the role and usefulness of fetal heart-rate monitoring in

women presenting with APH. In one study, the fetal heart-rate pattern (CTG) was abnormal in 69% of women

presenting with placental abruption. Whilst conservative (expectant) management appears to be safe in

preterm pregnancies with placental abruption and a normal CTG, an abnormal CTG is associated with poor

fetal outcome and delivery should be expedited to save the fetus.

Clinical judgement is required in these

circumstances since women presenting with bleeding that may indicate a catastrophic event such as

placental abruption, constitute a group where the fetus is more likely to be exposed to severe hypoxia and

acidaemia. In such circumstances, the CTG can reasonably be expected to be informative.

Labour and delivery

When should women with APH be delivered and what mode of delivery should be employed in women

whose pregnancies have been complicated by APH?

If fetal death is diagnosed, vaginal birth is the recommended mode of delivery for most women

(provided the maternal condition is satisfactory), but caesarean birth will need to be considered for

some.

If the fetus is compromised, a caesarean section is the appropriate method of delivery with concurrent

resuscitation of the mother.

Women with APH and associated maternal and/or fetal compromise are required to be delivered

immediately.

The optimum timing of delivery of women presenting with unexplained APH and no associated maternal

and/or fetal compromise is not established.

A senior obstetrician should be involved in determining the

timing and mode of birth of these women.

In women with APH secondary to placenta praevia, intrapartum management is described in Green-top

Guideline No. 27

APH associated with maternal or fetal compromise is an obstetric emergency. Management should include

maternal resuscitation and delivery of the fetus to control the bleeding. Delivery in this situation will usually be by caesarean section, unless the woman is in established labour. Similarly, if there is

evidence of fetal distress, resuscitation of the mother should commence and arrangements made to deliver

the baby by caesarean section once the woman is stabilised.

Definition

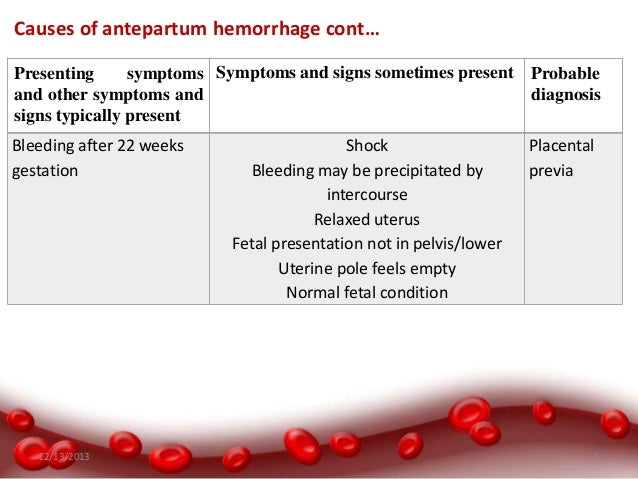

- Placenta previa is a condition wherein the placenta of a pregnant woman is implanted abnormally in the uterus. It accounts for the most incidents of bleeding in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Pathophysiology

- The placenta implants on the lower part of the uterus.

- The lower uterine segment separates from the upper segment as the cervix starts to dilate.

- The placenta is unable to stretch and accommodate the shape of the cervix, resulting in bleeding.

- Low lying placenta. The placenta implants in the lower portion instead of the upper portion of the uterus.

- Marginal implantation. The placenta’s edge is nearing the cervical os.

- Partial placenta previa. A portion of the cervical os is already covered by the placenta.

- Total placenta previa. The placenta occludes the entire cervical os.

Signs and Symptoms

The following signs and symptoms for placenta previa must be detected immediately by the health care providers to avoid risking the life of the fetus.

- Bright red bleeding. When the placenta is unable to stretch to accommodate the shape of the cervix, bleeding will occur suddenly that could frighten the woman.

- Painless. Bleeding in placenta previa is not painless and may also stop as abruptly as it had begun.

Diagnostic Tests

To diagnose placenta previa, the patient must undergo the following diagnostic procedure.

- Ultrasound. Early detection of placenta previa is always possible through ultrasonography. It is the most common and initial diagnostic test that could confirm the diagnosis.

Medical Management

Medical interventions are necessary to ensure that the safety of both mother and fetus are still intact.

- Intravenous therapy. This would be prescribed by the physician to replace the blood that was lost during bleeding.

- Avoid vaginal examinations. This may initiate hemorrhage that is fatal for both the mother and the baby.

- Attach external monitoring equipment. To monitor the uterine contractions and record fetal heart sounds, an external equipment is preferred than the internal monitoring equipment.

Surgical Management

Surgical interventions are carried out once the condition of both the mother and the fetus has reached a critical stage and their lives are exposed to undeniable danger.

- Cesarean delivery. Although the best way to deliver a baby is through normal delivery, if the placenta has obstructed more than 30% of the cervical os it would be hard for the fetus to get past the placenta through normal delivery. Cesarean birth is then recommended by the physician.

Nursing Assessment

- Assess baseline vital signs especially the blood pressure. The physician would order monitoring of the blood pressure every 5-15 minutes.

- Assess fetal heart sounds to monitor the wellbeing of the fetus.

- Monitor uterine contractions to establish the progress of labor of the mother.

- Weigh perineal pads used during bleeding to calculate the amount of blood lost.

- Assist the woman in a side lying position when bleeding occurs.

Nursing Interventions

- Assess fetal heart sounds so the mother would be aware of the health of her baby.

- Allow the mother to vent out her feelings to lessen her emotional stress.

- Assess any bleeding or spotting that might occur to give adequate measures.

- Answer the mother’s questions honestly to establish a trusting environment.

- Include the mother in the planning of the care plan for both the mother and the baby.

0 comments