Diverticular Disease

11:21:00 AM

What is diverticular?

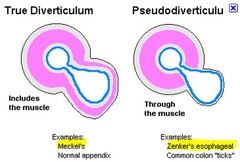

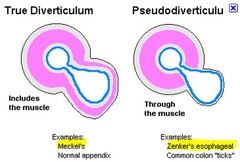

It is an outpouching of the colonic mucosa and the underlying connective tissue through the colon wall.

Diverticular disease is acquired outpouching which makes them a false diverticular.

Although diverticula can occur anywhere in the large bowel, they usually occur in the sigmoid portion of the colon.

They rarely occur below the peritoneal reflection and involve the rectum. Diverticula vary in diameter but typically are 3 to 10 mm in size. Giant diverticula, which are extremely rare, are defined as diverticula > 4 cm in diameter; sizes up to 25 cm have been reported. People who have colonic diverticulosis usually have several diverticula.

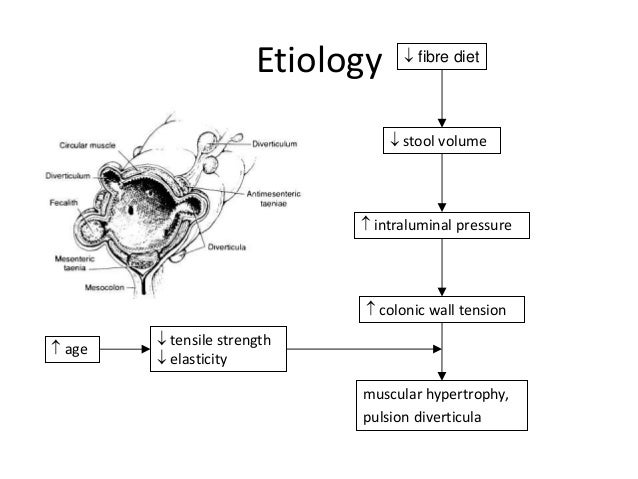

Diverticulosis becomes more common with increasing age; it is present in three-quarters of people > 80 years.

Diverticula are possibly caused by an increase in intraluminal pressure, which leads to mucosal extrusion through the weakest points of the muscular layer of the bowel—areas adjacent to intramural blood vessels.

Most (80%) patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic or have only intermittent constipation. About 20% become symptomatic with pain or bleeding when inflammatory or hemorrhagic complications develop.

Patients with diverticulosis sometimes develop nonspecific GI symptoms, including abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhoea, and passage of mucus from the rectum.

This constellation is sometimes referred to as symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD). However, some specialists believe these symptoms are due to another disorder (eg, irritable bowel syndrome), and the presence of diverticula is coincidental rather than causal.

Complications of diverticulosis

Complications of colonic diverticular disease are more common among people who smoke, are obese, or use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Complications occur in 15 to 20% of patients and include

- Diverticulitis -painful inflammation of a diverticulum. It may be uncomplicated or complicated.

- Diverticular bleeding (occurs in 10 to 15% of patients with diverticulosis)

- Segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease -refers to manifestations of colitis (eg, hematochezia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea) that develop in a few (1%) patients with diverticulosis.

Diverticular Bleeding

Diverticular bleeding is the most common cause (up to 50%) of brisk lower GI bleeding in adults. A study showed that the cumulative incidence of lower GI bleeding from diverticulosis was about 2% at 5 years and 10% at 10 years.

The pathophysiology of diverticular bleeding is unknown, but several mechanisms are hypothesized, including:

NSAIDs have been reported to increase the risk of haemorrhage.

Although most diverticula are in the distal (left) colon, half of diverticular bleeding occurs from diverticula in the proximal (right) colon. Patients with pancolonic diverticulosis have a higher incidence of bleeding.

Diverticular bleeding manifests as painless hematochezia. Because the bleeding vessel is an arteriole, the amount of blood loss is usually moderate to severe. Fresh blood or maroon-coloured stool is the typical manifestation; rarely, right-sided diverticular bleeding can manifest as melena. Diverticular bleeding usually occurs without concomitant diverticulitis.

The majority (75%) of episodes of bleeding cease spontaneously. The remainder requires intervention, typically endoscopic.

Patients who have had a diverticular bleeding episode have an increased risk of rebleeding.

Diagnosis

Asymptomatic diverticula are usually found incidentally during colonoscopy, capsule endoscopy, barium enema, CT, or MRI.

Lower GI bleeding due to diverticulosis is suspected when painless rectal bleeding develops, particularly in an elderly patient or in a patient who has a history of diverticular disease. Evaluation of lower GI bleeding typically includes colonoscopy, which can be done after rapid colonic preparation: 4 to 6 L of polyethylene glycol solution delivered orally, ideally via a nasogastric tube, and given over 3 to 4 hours until the rectal effluent is clear of blood and stool. If the source cannot be seen with colonoscopy and ongoing bleeding is sufficiently rapid (> 0.5 to 1 mL/minute), CT angiography or radionuclide imaging may localize the source.

Treatment

Asymptomatic diverticulosis requires no treatment or dietary changes. There is no association between the consumption of nuts, seeds, corn, or popcorn and diverticulitis, diverticular haemorrhage, or uncomplicated diverticulosis, and avoidance of these foods is no longer recommended.

For diverticulosis with nonspecific GI symptoms, treatment is aimed at reducing spasm of a segment of colon. A high-fibre diet is often recommended and may be supplemented by psyllium seed preparations or bran. However, the role of fibre in the treatment of diverticulosis is limited. In general, data are inadequate to confirm the beneficial effects of fibre.

Antispasmodics (eg, belladonna) are not of benefit and may cause adverse effects. Low-fibre diets are not helpful.

Surgery is unwarranted for uncomplicated disease except for giant diverticula.

Treatment of Diverticular Bleeding

Diverticular bleeding stops spontaneously in 75% of patients.

Initial management is as for lower GI bleeding. Treatment of diverticular bleeding is often given during the diagnostic procedure. Colonoscopic identification of a bleeding site (which can occur up to 20% of the time) allows for endoscopic options to control bleeding, including epinephrine injection, application of endoclips or fibrin sealant, heater probe or bipolar coagulation, and band ligation.

Angiography can help with the diagnosis of the source of bleeding and treatment of ongoing bleeding. During angiography, a number of techniques can be used to control the bleeding, particularly embolization and, less often, vasopressin injection. Embolization is successful about 80% of the time. Angiographic complications of bowel ischemia or infarction are less common (< 5%) with current super-selective catheterization techniques.

Surgery is rarely needed but is recommended for patients who have had multiple or persistent episodes of diverticular bleeding refractory to therapy or who have hemodynamic instability despite aggressive resuscitation.

If angiography or surgery is being considered, identifying the specific bleeding diverticulum endoscopically or using a nuclear medicine study during active bleeding gives direction to the interventional radiologist and may limit the size of a potential surgical resection.

When the bleeding site is known, the need for subtotal colectomy (with its associated higher morbidity and mortality) is markedly reduced because a hemicolectomy or segmental colectomy may be done instead. However, patients who have continued and life-threatening haemorrhage and no identifiable bleeding diverticulum may require a subtotal colectomy.

0 comments